shogihax - Remote Code Execution on Nintendo 64 through Morita Shogi 64

Initial publication: May 3rd, 2020Introduction

I've been wanting to develop Nintendo 64 homebrew for a while, but have been put off due to the limited options available for testing on the hardware.

Instead of shelling out money for a flashcard (which have inflated prices since they are marketed for pirating games), I decided to invest some time systematically going through other potential methods of running arbitrary code.

I eventually stumbled upon Morita Shogi 64, the only official N64 game to include a modem built-into the cartridge to support its unique online-play functionality. The ability to easily transfer arbitrary data to the game through this interface made it an attractive target to analyse. Note that Nintendo also produced a stand-alone modem cartridge which allows the 2 supported N64DD games to connect to the internet (Randnet and Mario Artist: Communication Kit), but since the N64DD was cancelled after only 10 games were released for it in Japan it's very rare and expensive, making it a less convenient choice than Morita Shogi 64.

In this article I will describe how I exploited the game for arbitrary remote code execution, ultimately creating a solution for developing and testing small programs on the console that under my criteria is preferable to the other options. The code is available on GitHub.

Much like in my last post, where I developed the first PS2 exploit that could be triggered using only hardware that came with the original console release (in PAL regions), I compromise on a lot of other criteria such as transfer speed that makes this solution impractical to many; to those people, I hope this article is still interesting for the novelty value at least, and I'm sure we can all agree that it's more convenient to use than the only other 2 public N64 arbitrary code execution exploits that don't require unofficial hardware: the one developed against the game The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, which is triggered entirely from controller input, and the one for Pokemon Stadium, which is triggered through the Game Boy save import feature. Unlike my PS2 exploit, which was for PAL regions only, this one is for NTSC regions only, so hopefully this balances things out.

GameShark

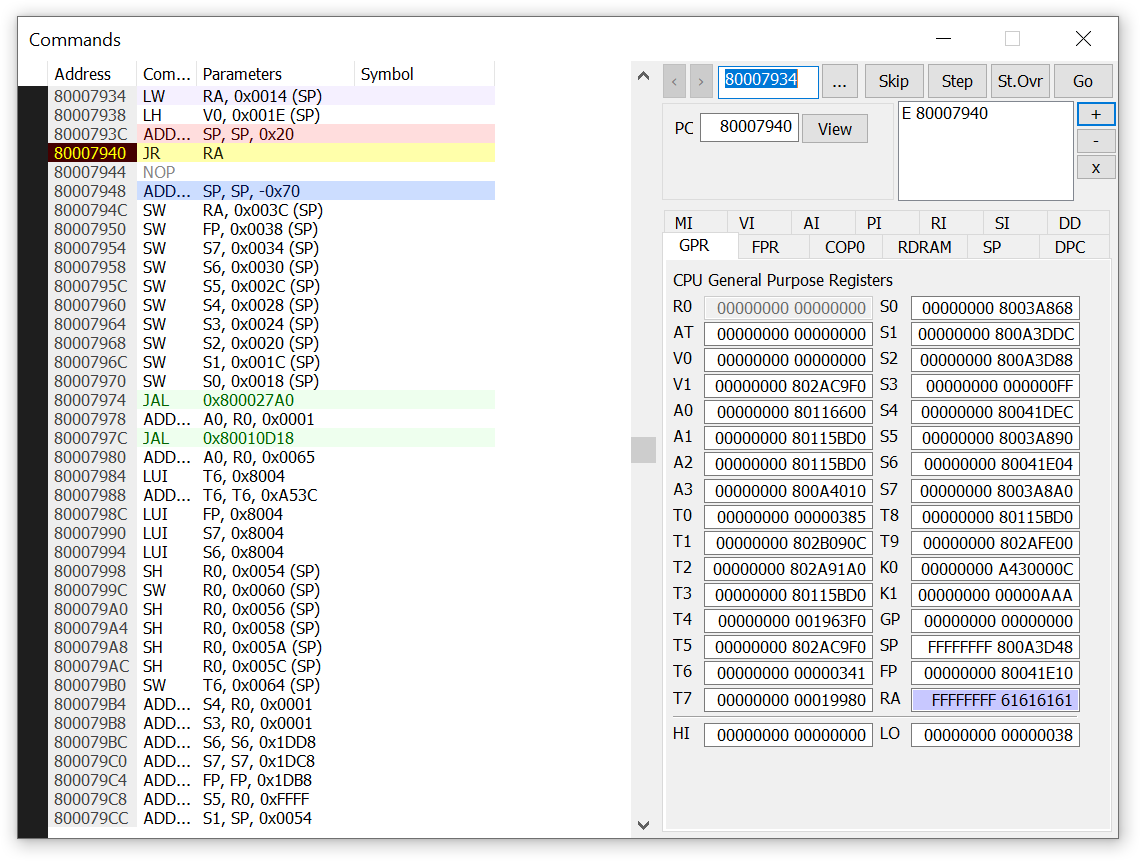

Since the modem hardware isn't supported by the Project 64 Nintendo 64 emulator, I had to perform all of my testing on the real hardware. Rather than trying to exploit the game using only static analysis, I made use of a GameShark early on to provide some dynamic feedback.

There exist specific models of Action Replay/GameShark cheating devices which expose read/write functionality over a parallel port on the back of the cartridge. Unfortunately, these are difficult to find since they were only produced for a brief period, before the functional parallel ports were replaced with non-functional dummy ports, making it impossible to identify them without opening up the cartridge. Even if you can find one of these, you'll also either need an old PC with a parallel port to connect to, or a very specific and no longer stocked parallel port to USB adapter containing a MosChip MCS7705 controller in order to get it working with a modern computer.

ppcasm sent me one of these for experimentation, but it ended up being pretty painful to use due to unreliability (even after fixing a couple of bugs) and low throughput (single digit bytes-per-second transfers). I used this for a while, before it eventually broke, as they are notorious for. Regardless, I had some basic way of partially debugging Morita Shogi 64 on the hardware for a while, which was invaluable.

Being able to write to RAM allows you to run homebrew programs, and being able to read RAM provides the ability to monitor execution. Whilst it should be technically possible to extend this to create a full execution-stepping debugger with read/write/execute breakpoints and a crash handler, this was out of scope of this project, so I relied only on the basic read/write functionality.

Note that these also require the expansion pak, an add-on which doubles the N64's RAM from 4MB to 8MB! This makes the N64 a really fun system to mod/debug since you have your own exclusive area of RAM which is essentially guaranteed not to be used by the game you're debugging.

Save data exploits

Many games, including Morita Shogi 64, use on-cartridge chips as a method of storage that persists across power cycles to save in-game progress (or alternatively the controller pak attached to the controller). Another avenue I had considered early on was exploiting the game over its loading of this cartridge save data.

Finding a vulnerability in a game's handling of save data is relatively trivial. Most games only consider this storage accessible to the game and so make little to no effort to validate contents other than a checksum. Even games which do attempt to validate contents often do so inconsistently due to the limited security experience during this era. Nintendo clearly didn't attempt to check for these vulnerabilities during quality assurance testing, and so it could almost be considered a by-design attack vector that if you can modify the contents of a game's save data that you can run your own code.

For example, Super Mario 64 is fully decompiled so I took a quick look and was able to find a write to an out of bounds pointer if sSoundMode (offset 0x1d1, 1 byte) is too large, which can be triggered by pressing the sound option box on the file select screen. That can be used to NOP out some code in the title screen renderer, but I gave up trying to exploit that - maybe someone reading will be interested in the challenge... if you could do it, you could potentially make a payload that patches Mario's colour to green to 'unlock Luigi' on a real cartridge, a feat people have been attempting since its release in 1996!

However, the limitations of this approach are clear: modifying save data requires unofficial hardware (like this open source Arduino project provided by Sanni), and the size of the save data is severely limiting (on-cartridge storage chips range from 512-byte EEPROM chips to 128KB FlashRAM, and controller paks are 32KB). The payload for a save data exploit would need to fetch more data, possibly over the transfer pak (which allows the N64 to access Game Boy cartridges through the controller), or through the modem in the case of Morita Shogi 64 (but if the game has a modem anyway, why not just exploit that?).

Morita Shogi 64 save game exploit

In this case, the game has 512 bytes of EEPROM storage, which is used to save the configured phone number and login details. I first decided to take a quick look at how the game reads this data, so that I'd at least know that the game can be exploited that way before purchasing it.

After some quick reverse engineering, I located the checksum function at 0x8000eaa0, and built a quick program to allow me to modify a save and correct the checksum so it would be accepted by the game.

With the ability to correct the checksum, I extended the phone number string, and sure enough triggered a stack buffer overflow by navigating to the phone number input menu.

This save data exploit can be triggered more quickly than the pure-modem exploit, so it could be a nice way to 'install' the exploit more permanently.

Reversing the packet handling

Okay, you didn't come here to read about a save game exploit, so I'll move onto the more interesting target, handling of controllable packet data over the built-in modem.

Firstly, we'll need a system to actually send and receive controlled data to the N64 over the modem. If you're comfortable modding a USB modem to simulate the line voltage (as has been documented on other retro modem communities like DreamPi), that's the most practical solution to use. Alternatively, you could just connect the N64 to your phone socket as normal and communicate over your phone; since the exploit is deterministic, you could just encode the data as an audio file and play it through the microphone without requiring any custom software. ppcasm talks more about these methods on his blog.

With that setup, let's get into the reversing! Like many N64 games, Morita Shogi 64 is utilising compression, so to reverse the code for the online mode, we'll select it from the menu and then take a RAM dump from the emulator.

Debug prints

The first thing that becomes apparent when firing up that RAM dump in Ghidra is the fact that the game left in a bunch of debug printing calls. You can search for strings like "packet", and locate all of the networking code fairly easily.

More interestingly, we can actually access the output of these print calls on real hardware using the aforementioned GameShark parallel port functionality.

By hooking the gamePrint function (0x800029d0):

/*

la $v0, 0x80410000

jr $v0

nop

*/

unsigned char gamePrintHook[] = {0x3c, 0x02, 0x80, 0x41, 0x00, 0x40, 0x00, 0x08, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00};

WriteRAM(g, gamePrintHook, 0x800029d0, sizeof(gamePrintHook));

WriteRAM(g, gamePrintHook, 0xA00029d0, sizeof(gamePrintHook));And inserting some code to save the passed arguments to unused expansion RAM:

/*

lw $v1, -4($v0)

sw $a0, 0($v1)

sw $a1, 4($v1)

sw $a2, 8($v1)

addiu $v1, $v1, 12

sw $v1, -4($v0)

jr $ra

nop

*/

unsigned char printer[] = {0x8c, 0x43, 0xff, 0xfc, 0xac, 0x64, 0x00, 0x00, 0xac, 0x65, 0x00, 0x04, 0xac, 0x66, 0x00, 0x08, 0x24, 0x63, 0x00, 0x0c, 0x03, 0xe0, 0x00, 0x08, 0xac, 0x43, 0xff, 0xfc, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00};

WriteRAM(g, printer, 0x80410000, sizeof(printer));

WriteRAM(g, printer, 0xA0410000, sizeof(printer));

unsigned char start[] = {0x80, 0x41, 0x00, sizeof(printer)};

WriteRAM(g, start, 0x80410000 - 4, 4);We can pause the game at an arbitrary point and retrieve a list of all debug prints executed since our last observation:

printf("Hooked gamePrint, enter to dump\n");

Disconnect(g);

while(1) {

getchar();

if (!InitGSCommsNoisy(g, RETRIES, 1)) {

printf("Init failed\n");

do_clear(g);

return 1;

}

printf("Connected, dumping\n");

unsigned char end[4];

ReadRAM(g, end, 0x80410000 - 4, 4);

unsigned int endI = (end[0] << 24) | (end[1] << 16) | (end[2] << 8) | (end[3]);

unsigned int prints = (endI - (0x80410000 + sizeof(printer))) / 12;

printf("%d prints made\n", prints);

int i = 0;

for(; i < prints; i++) {

printf("%d / %d:\n", i, prints);

unsigned char r0[4] = {};

ReadRAM(g, r0, 0x80410000 + sizeof(printer) + i * 12 + 1, 3);

unsigned int r0n = (0x80 << 24) | (r0[0] << 16) | (r0[1] << 8) | (r0[2]);

char *s = readString(g, r0n);

printf("r0: %08x - %s\n", r0n, s);

int ps = 1;

for(int p = 0; p < strlen(s) && ps < 3; p++) {

if(s[p] == '%') {

unsigned char r[4] = {};

ReadRAM(g, r, 0x80410000 + sizeof(printer) + i * 12 + ps * 4, 4);

unsigned int rn = (r[0] << 24) | (r[1] << 16) | (r[2] << 8) | (r[3]);

if(s[p + 1] == 's') {

printf("r%d: %08x - %s\n", ps, rn, readString(g, rn));

}

else printf("r%d: %08x\n", ps, rn);

ps++;

}

}

printf("\n");

}

WriteRAM(g, start, 0x80410000 - 4, 4);

Disconnect(g);

}

I later sped this up by caching strings on the PC, and modifying the hook to ignore a bunch of high frequency, noisy, prints:

// avoid noisy prints

unsigned char printer[] = {0x80, 0x83, 0x00, 0x00, 0x24, 0x0c, 0x00, 0x80, 0x01, 0x82, 0x08, 0x2a, 0x14, 0x20, 0x00, 0x36, 0x3c, 0x03, 0x80, 0x0c, 0x34, 0x63, 0xf3, 0xf8, 0x10, 0x83, 0x00, 0x33, 0x3c, 0x03, 0x80, 0x0c, 0x34, 0x63, 0xee, 0x9c, 0x10, 0x83, 0x00, 0x30, 0x3c, 0x03, 0x80, 0x0c, 0x34, 0x63, 0xdf, 0x40, 0x10, 0x83, 0x00, 0x2d, 0x3c, 0x03, 0x80, 0x04, 0x34, 0x63, 0x1d, 0xec, 0x10, 0x83, 0x00, 0x2a, 0x3c, 0x03, 0x80, 0x0c, 0x34, 0x63, 0xc8, 0xf0, 0x10, 0x83, 0x00, 0x27, 0x3c, 0x03, 0x80, 0x0c, 0x34, 0x63, 0xcf, 0xa0, 0x10, 0x83, 0x00, 0x24, 0x3c, 0x03, 0x80, 0x0c, 0x34, 0x63, 0xcf, 0xb4, 0x10, 0x83, 0x00, 0x21, 0x3c, 0x03, 0x80, 0x0c, 0x34, 0x63, 0xd0, 0x38, 0x10, 0x83, 0x00, 0x1e, 0x3c, 0x03, 0x80, 0x0c, 0x34, 0x63, 0xcc, 0xc4, 0x10, 0x83, 0x00, 0x1b, 0x3c, 0x03, 0x80, 0x0c, 0x34, 0x63, 0xd0, 0x84, 0x10, 0x83, 0x00, 0x18, 0x3c, 0x03, 0x80, 0x0c, 0x34, 0x63, 0xd0, 0xb8, 0x10, 0x83, 0x00, 0x15, 0x3c, 0x03, 0x80, 0x0c, 0x34, 0x63, 0xde, 0x98, 0x10, 0x83, 0x00, 0x12, 0x3c, 0x03, 0x80, 0x0c, 0x34, 0x63, 0xde, 0x3c, 0x10, 0x83, 0x00, 0x0f, 0x3c, 0x03, 0x80, 0x0c, 0x34, 0x63, 0xdf, 0x34, 0x10, 0x83, 0x00, 0x0c, 0x3c, 0x03, 0x80, 0x0c, 0x34, 0x63, 0xd0, 0xd4, 0x10, 0x83, 0x00, 0x09, 0x3c, 0x03, 0x80, 0x0c, 0x34, 0x63, 0xd1, 0x04, 0x10, 0x83, 0x00, 0x06, 0x8c, 0x43, 0xff, 0xfc, 0xac, 0x64, 0x00, 0x00, 0xac, 0x65, 0x00, 0x04, 0xac, 0x66, 0x00, 0x08, 0x24, 0x63, 0x00, 0x0c, 0xac, 0x43, 0xff, 0xfc, 0x03, 0xe0, 0x00, 0x08, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00};

With this setup, I was able to observe helpful error messages such as "HEADER: Invalid CRC. %d\n", "HEADER: Invalid seq. number.\n", and others.

Packet handling overview

The debug strings made it fairly simple to reverse engineer how to establish a connection and begin sending valid packets to the game.

When you click the menu item to enter online mode, it transfers control to the looping function, online (0x800ab998).

This function calls connectPackets (0x800bbb1c) which handles all the connection and initial packet handling of top-level commands. There's not too much interesting stuff during the initial connection handling, it just expects some magic data to ensure that it's talking to an intended server. If you send invalid data during the connection phase it will tell you how to correct it by printing "modem receive char %02x, expect char %02x\n".

Once connection has been established, the online function then goes on to actually handle top-level packets (a 10-byte header followed by data). Every few milliseconds when the game loops around to calling this function, it will take all received data and try to construct a packet (a 10-byte header followed by data). Since we're only able to send a certain amount of data during this time interval, our packet sizes are restricted to around 80 - 100 bytes.

Building upon those raw packets, the game implements a system to construct larger, multi-packet, messages, and then starts passing them to handleSubCommandPacket (0x800aea40).

Top-level commands

Top-level commands operate on single packets, and are the first commands I started reversing. There are 11 of these commands, and due to the debug prints, we have the official names for most of them, which are:

1 = ?

2 = NS_ACK

3 = NS_RETRY

4 = NS_ABORT

5 = NS_CONNECT

6 = NS_DISCONNECT

7 = ?

8 = NS_LOGINOK

9 = ?

10 = NS_LOGINFAIL

11 = ?

Once we're established a connection, we need to send an NS_CONNECT, and an NS_LOGINOK packet to enable access to packet type 7, which is the main packet type and will be discussed later. There are a few interesting things with these top level commands before moving on.

NS_CONNECT

This top-level command takes two unsigned shorts from the packet and computes a heap allocation size. This is vulnerable to integer overflow which leads to heap buffer overflow. Great! The very first command we send has a vulnerability.

It passes those sizes to 0x800bb18c, which is allocating space for future packet structures:

alloc = allocateMemory(PTR_LOOP_80056ea4, totalPacketSize * packetCount * 2);

if (alloc == (uint *)0x0) {

packetAlloc = alloc;

return 0xffffffffffffffff;

}In the end, I didn't play with this vulnerability too much, but I believe it's probably exploitable.

NS_DISCONNECT

The disconnect command basically just accepts a string from the packet and copies it to a statically reserved 256-byte buffer (&disconnectString = 0x800d39a0):

case 6:

disconnectReason = *(undefined4 *)(packetData + 10);

sequenceNumberAnticipating = uVar7;

copyString((byte *)disconnectString,packetData + 0xe);

gamePrint(s_HEADER:_DISCONNECT:_%d(%s)_800cf2f8,disconnectReason,

disconnectString);

gamePrint(&DAT_800cf314);

disableNetworking();

resetPacketVariables();

connectionState1 = 0xf;

DAT_800cac08 = 5;

return;

There's no bounds checking on the copyString call, so we could potentially overflow the disconnectString. Unfortunately, since this is a top-level command, we can't send very large packets, and so this doesn't turn out to be very useful. We can also trigger a crash by sending an unterminated string, but don't think that's easily exploitable either.

Multi-packets

Whilst we've already found some interesting bugs, let's dig deeper into the code. After connecting and logging in, we can start sending the top-level command number 7; this command is used to send higher level commands which can operate on larger, multi-packet, messages.

The logic for reconstructing multi-packets is in handleMultiPackets (0x800bae08). Byte 1 of each packet is a flags bitmap which recognises the following:

1 - start

2 - end

4 - multi

128 - ack

A single packet can be sent and processed immediately by using flag 0, but to send larger messages (of up to 0x1000 bytes), it needs to be split up into multiple packets and then reconstructed by this function. The first packet will have flag 5 (multi | start), the middle packets will have flag 4 (multi), and the final packet will have flag 6 (multi | end).

One thing that will be useful later is that by delaying the final packet, we can construct a large area of controlled packet memory and leave it there for an arbitrary length of time, before finally triggering processing of the message by sending the final packet.

Commands and subcommands

Top-level command 7 (I'm calling it NS_COMMAND), allows us to send the following subcommands:

MN, LS, ME, ED, IF, GS, GM, ML, BB, DL, FC, DC

We're getting pretty deep into the game now - for example, I sent a GS command and it actually started an online game match for the first time in 20 years:

modem.subcommand('GS', 0x000e, '\x00\x00\x00\x09', '\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00')

Calling most of these commands with invalid data will crash. Since these commands branch off quite far, I didn't fully analyse all of these crashes; there were a few NULL dereferences, but I guess some of the others might be exploitable.

There's also reference in the code to a DG (debug) command, which allows you to read and write out of bounds, but unfortunately this command is not enabled (its code is still present at 0x800b4354, but they zeroed its entry in the array of valid command names at 0x800ca3d0).

Command IF

The IF command (0x800b3e94) is the simplest command, it basically takes two strings, and opens a dialog box on screen, much like the NS_DISCONNECT top-level command. Unlike the NS_DISCONNECT overflow however, this is a command handled through NS_COMMAND and so can take a large controlled packet. It also copies to stack destinations, giving us stack buffer overflows instead of static array overflows.

The relevant parts of the function look like this:

void *commandIF(char *packet) {

char final[256];

char otherString[100];

char target[108];

char *packetPtr;

packetPtr = packet;

...

copyAdvanceString(&packetPtr, target);

copyAdvanceString(&packetPtr, otherString);

final[0] = 0;

strcat(final, &start);

strcat(final, otherString);

strcat(final, &mid);

strcat(final, target);

strcat(final, &end);

openDialog(final, 1);

...

}

copyAdvanceString calls copyString and then advances the source pointer by the length copied. The copyString function is similar to strcpy, but has special handling for a custom Japanese character encoding that maps input characters above 0x80 to multi-byte character outputs. This limits our ability to craft fully arbitrary addresses.

Exploitation

Initial setup

Since we're testing on real hardware and can't observe how the game crashes with our primitive GameShark debugger setup, we need a very simple payload which can verify control flow redirection. The simplest thing I came up with was calling disableNetworking (0x8001da9c), which turns off the red light on top of the cartridge.

In addition, we can use the GameShark's arbitrary write to place this payload at a character encodable address like 0x80313130, so that we don't need to deal with the character conversion behaviour of copyString initially.

Overflow

Exploitation of the IF command seems straightforward, we can overflow the target string on the first copy by specifying a large first string, eventually corrupting a return address on the stack. Then when the function returns it will redirect control flow to our corrupted address.

Overflowing that much data will also corrupt packetPtr, which is used as the source pointer for the next copy, before returning to our corrupted address, so in order to not crash on the second copy we'll need to make sure to write a valid address that points to an empty string there.

With all of that in mind, I tried the following:

packetPtr = '\x80\x05\x0d\x01'

returnAddress = '\x80\x31\x31\x30'

modem.subcommand('IF', 0x000e, '\x00\x00\x00\x09', 'A' * 108 + packetPtr + 'C' * 0x24 + returnAddress + '\x00' + 'B' + '\x00')

And... It didn't work. I was stumped for a while on this, before I decided to try using a GameShark code to NOP-out the call to openDialog so that we would directly return after performing the second copy (a10b3fb4 0000, a10b3fb6 0000), which worked! It turns out that there's additional special handling in openDialog which crashes the game if we try to display invalid characters (such as 0x80), further limiting the type of corruption we can perform with the overflow.

Removing the GameShark

At this stage we've demonstrated using the vulnerability to redirect control flow, but we rely on the GameShark for a couple of things: placing our payload at a nicely encodable address, and removing the limitation on using invalid characters.

The two limitations are intrinsically linked, and could be carefully worked around together by ensuring we only use valid characters, and padding the payload where possible to help achieve this. For example, instead of using input character 0x80 which maps to the invalid output character 0x80, we could use input character 0xef 0x1f, which maps to valid output character 0xfd 0x80. That works fine if we want the first byte to be 0x80 and don't care about corrupting the previous byte to 0xfd, but it could be a problem if we needed say the final byte to be 0x80 instead (in that case it would make more sense to just pad the start of the payload by 0x84 bytes so that the final byte was 0x04).

However, thankfully there's a much more elegant solution we can use to eliminate the second requirement. If we trigger a second stack buffer overflow during the copy into otherString, we can overflow into target and rewrite the string so that it doesn't contain any invalid characters before it is displayed (even just immediately terminating it to produce an empty string). Note that at this point we're no longer necessarily copying from the packet, since we have corrupted packetPtr, we just need to redirect packetPtr to any string in memory that's larger than 100 bytes and consists of only valid characters. There are plenty of suitable strings.

The final string constructed after the double stack buffer overflow will just be start + 'x' * 100 + mid + '' + end, which won't cause any crash in openDialog, and will let us successfully return to our corrupted return address.

Now that we don't need to worry about encoding invalid characters, we can use the GameShark's memory search cheat feature to find which areas of memory our packet data resides in. Our fully constructed message is at 0x801bd91c, which is difficult to use since that address contains character 0xd9, but some of the individual packets (including their headers) are still in memory and are located at an easily encodable address region to corrupt the return address to (around 0x800a7500). Since we control 80 bytes of data, that's easily enough to place a 'stage 1' payload which flushes to instruction cache the full contiguous, message at 0x801bd91c ('stage 2') and then jumps to it.

Cache coherency

All you need to know is that there are 2 virtual address mappings to access memory on the N64, from 0x80000000 is the cached region, and from 0xa0000000 is the uncached region. Depending on whether you read/write or execute from the cached region, the system will use either the data cache, or instruction cache, respectively.

A write to 0x80000000 will just write to the data cache, but may not immediately commit it to RAM, and so reading 0xa0000000 might give you a stale value. If you then jump to 0x80000000, you'll execute from the instruction cache, which may not have the latest data from RAM. We need to ensure that when we redirect control flow to our payload, that we are actually executing our payload and not stale data.

Our payloads are written to the cached virtual address mapping and so we can only guarantee that it resides in the data cache. However, remembering that the vulnerability is only triggered when we submit the final packet which has the end flag set in its header, we can upload all of the data for our IF command packet, including the stage 1 and 2 payloads, and leave them in memory for an arbitrary length of time before choosing to trigger the double stack buffer overflow. Leaving the payloads for a few seconds gives us strong confidence that they will have been committed from data cache to main memory in that time. To then ensure we don't use stale instruction cache, we redirect the return address to jump to the uncached virtual address for stage 1.

As mentioned before, once we're executing stage 1, there's enough space to write-back the data cache to RAM, and invalidate the instruction cache so that we can execute stage 2 utilising caching.

Writing a loader

At the point of jumping to stage 2, we're executing up to almost 0x1000 bytes of arbitrary code (subtract a little for the overflow data).

Stage 2 can use the game's existing getCharFromModem (0x8001dd48), and sendModem (0x8001df54) functions to fetch a further (stage 3) payload, without any strict size limitation. Since other threads from the game are still running, I decided to write the payload to expansion RAM to ensure that we have exclusive access and it isn't corrupted by unrelated code.

Once this third stage payload has been downloaded, stage 2 can disable interrupts, relocate stage 3 to the beginning of RAM, writeback the data cache to RAM and clear the instruction cache, and then execute it! We also have enough space in stage 2 to implement decompression of stage 3, which makes it much faster to download.

Full source code for stage 2 can be found in the repository.

Stage 3

Stage 3 can be an arbitrary size, so you can make whatever program you like here. There are a few gotchas from loading a raw binary rather than writing a full ELF loader to keep in mind when making a stage 3, so I'll briefly address those:

- I jump to offset

0of the payload as the entry point, you should write a shortcrt0.sstyle assembly routine at.section .text.startupto ensure that its at offset0in the output (initialiseSPand jump tomainat least), - I don't bother zeroing the

.bsssection so either don't rely on your global variables being initialised to0, or you could include the.bsssection in your output binary and hope the compression keeps the size down, - When compiling MIPS payloads pass

-G 0to ensure that your payload doesn't referenceGPwhich my loader doesn't initialise,

For the initial release, I've made a hacky proof-of-concept 'Homebrew Channel' stage 3, which demonstrates drawing to a double buffered framebuffer, and downloading/uploading data over the modem, but the possibilities here are endless... Assuming you program the PC to forward your traffic on, you have an internet connected Nintendo 64!

Conclusion

Morita Shogi 64 was successfully exploited to provide the first UnPaTcHaBlE ReMoTe CoDe ExEcuTiOn exploit against the Nintendo 64 console.

This exploit allows a user to execute homebrew software on the console much faster and more conveniently than with arbitrary code execution exploits in games without modems, like Zelda, and without having to purchase inaccessible, expensive, unreliable, and unofficial hardware like a GameShark parallel port and USB adapter, or a "flashcard".

Furthermore, once code execution has been achieved through this exploit, the developer has access to the unique modem functionality of the cartridge - this allows development of games which dynamically load more content than would be possible on a normal cartridge, or even implementing real-time online multiplayer functionality (which could perhaps be added to Super Mario 64 using the public decompilation).

With thanks to ppcasm.